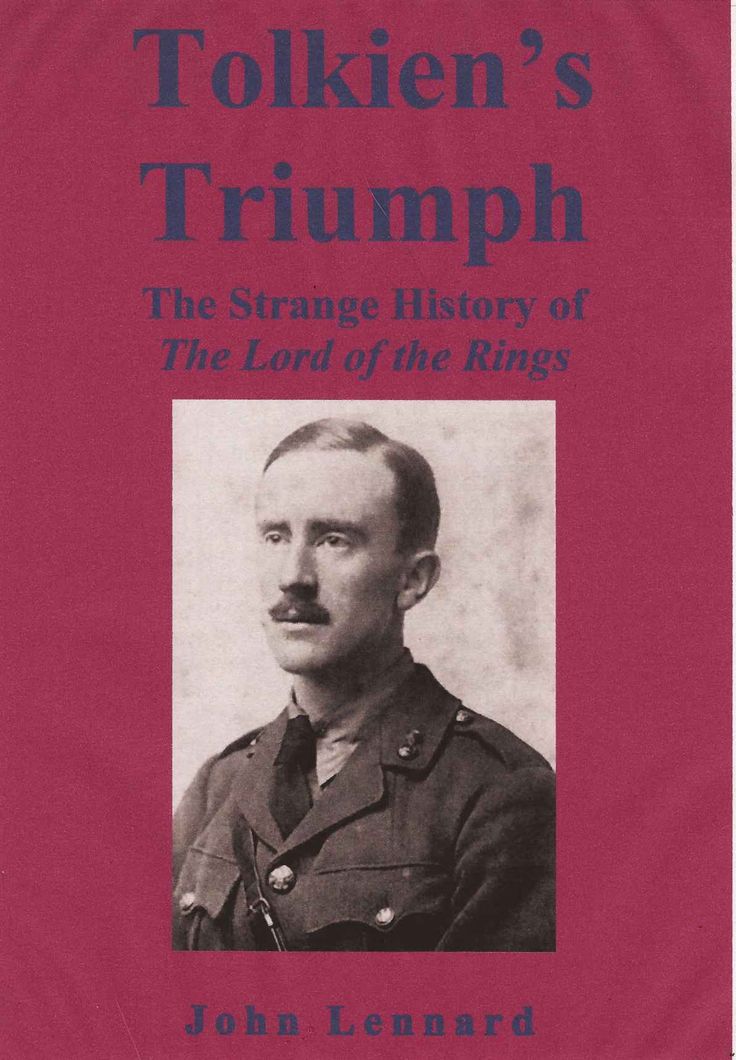

tolkien's Triumph: The Strange History of 'The Lord of the Rings' (01.09.14 by Simon Cook) -

Comments

What Lennard has to say about Tolkien is interesting; but it is the form of Tolkien’s Triumph that is really remarkable.

The paywall, which prevents dissemination of contemporary scholarship among the interested public, predates the internet. Lennard’s first book, But I Digress, was published some two decades ago by Oxford University Press. Supposedly a history of parentheses in English poetry, I am unlikely to ever read it because I have no access to a university library and to buy it would set me back $195.

The paywall is built into the fabric of academic publishing. While many academics complain about this state of affairs, Lennard is the first I know to take matters into his own hands. Turning to self-published ebooks distributed online, he now sets the cost of his books himself. The result is a staggering 97.4% reduction in price.

(As a parenthesis of my own, it’s refreshing to see the internet fulfilling some of its original promise as a force for good).

So what do you get for your 5 bucks? A short answer is four solid chapters, which include much interesting background relating to the astonishing popular success of The Lord of the Rings. A longer answer is an extended meditation around two distinct themes that, in my opinion, do not quite fit together.

On the one hand, Lennard discusses the compulsive hostility of the academic literary establishment toward Tolkien. Explicitly building on the arguments of Tom Shippey, he explains how modern literary criticism places ultimate value on the novel and its realistic study of character. As such, it is simply unable to comprehend what Tolkien is about. For Tolkien did not set out to explore the interior world of his subjects, did not try to write a novel, and in general found archaic forms of narrative adequate for the crafting of his stories.

On the other hand, Tolkien’s Triumph explores the tragic vision at the heart of Tolkien’s myth-making. Everything in Tolkien’s universe contains the seeds of destruction. Be it the creation of the Silmarils, the overreaching of Númenor, or the forging of the elven rings – all new shoots grow into trees that bear poisoned fruit. Tolkien’s stories thus become tales of heroic resistance in the face of inevitable doom. This theme, Lennard points out, reflects both Tolkien’s Old Northern literary models and his religious conviction of the profound significance of the fall.

Lennard explains how The Lord of the Rings is both distinct from yet ultimately a part of this tragic vision. This epic tale of the last war of the ring arose out of the demand for a sequel to The Hobbit, a story composed for children and most certainly not a tragedy. At first sight, The Lord of the Rings can appear a simple tale of victory over evil – and such indeed is the cinematic spectacle forged by Peter Jackson.

But in a compelling analysis of ‘The Scouring of the Shire’, the penultimate chapter of The Lord of the Rings the contents of which is entirely passed over by Jackson, Lennard shows how Tolkien deliberately brought his epic back into line with his underlying vision. ‘The Scouring of the Shire’ shows the shadow still at work even after the defeat of Sauron. In this final part of the tale of Saruman, Lennard argues, Tolkien shows us that there is no final victory over evil and that ultimately wars are always lost. The Lord of the Rings comes into view as at one with the great, cyclic series of tragedies known to us through The Silmarillion, with Jackson’s Hollywood ending a betrayal of Tolkien’s vision.

Lennard tries to take this argument a stage further, arguing that Tolkien himself was guilty of avoiding some of the more painful implications of his own vision. Frodo, for example, a classic war survivor, haunted by his memories and damaged psychically as well as physically, is supposedly given too easy an escape route – a ship that sails west over the ocean to the undying lands. Lennard argues that here, as elsewhere, Tolkien falls back upon “images of mystical healing beyond the bounds of Middle-earth” that “to one who does not share Tolkien’s religious faith” are not so very different “from the hazy dissolve into the sunset of Hollywood cliché.”

This insidious comparison of Tolkien with Jackson opens the door to a genuinely illuminating discussion of fan fiction, which Lennard hails as “at its best a highly creative form of criticism”. He discusses a number of “fics” that are said to tackle issues “that Tolkien left in a less than satisfactory state.”

Now, let me be clear. Lennard provides the first scholarly engagement with Tolkien fan fiction that I have encountered, and his is a sympathetic and illuminating discussion. It has even led me to start reading some of the fics – and I’ve been taken aback at how good they are. But I’ve found their differences from the genuine article illuminating. In particular, I’ve noted an absence of that magical quality that pervades Tolkien’s depictions of Middle-earth. And, surely related, I’ve also been taken aback by the extent to which these literary investigations of the post-war anguish of Frodo and others read rather like the kind of exploration of character identified by Lennard with the modern novel.

And there’s the rub. For all its wonderful qualities, the fan-fiction I have read belongs to a genre of non-magical realism. But Tolkien crafted fairy-stories and myths. Lennard is completely wrong to dismiss Tolkien’s vision of the undying lands beyond the great western ocean as merely a coping mechanism of religious faith. This conception of the relationship of our Middle-earth to faëry stands at the very foundation of tolkien's construction of an English mythology. It is the key to the magic of Middle-earth. To abandon it is perilous.

Lennard is quite correct to maintain that Tolkien was not trying to write a novel; but it seems to me that he does not fully grasp what it might mean that he was writing a fairy-story.

But you do not have to take my word for any of this. At $4.99 you can afford to judge for yourself. And I would recommend it.

Acknowledgments: thanks to @MissPritiJadeja @CalinLeafshade @oondir for helping me work out the % price reduction between Lennard’s first book and Tolkien’s Triumph.

Author: John Lennard

Sold by: Amazon Digital Services, Inc.

Publication Date: October 2013

Type: ebook, 217 pages

File Size: 1448 KB

ASIN: B00G3CBZSA

Author biography

Simon J. Cook is a professional editor and independent scholar. His other writings can be found via his website: https://yemachine.com.

Spread the news about this J.R.R. Tolkien article: