Interview with Douglas A. Anderson and Verlyn Flieger on Tolkien on fairy-stories (06.06.08 by Pieter Collier) - Comments

Verlyn Flieger and Douglas A. Anderson are both well-known Tolkien scholars, co-founders (with Michael Drout) of Tolkien Studies.

Anderson's most recent books include The Annotated Hobbit (HarperCollins UK, 2003) and the anthology Tales Before Tolkien: The Roots of Modern Fantasy (ballantine

US, 2003; mass market edition 2005).

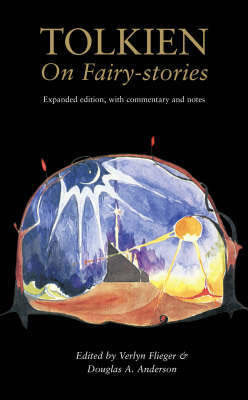

Put these two top class Tolkien scholars together and you can expect something wonderful to happen. In this case I'm glad to announce the cooperation resulted into a book called 'Tolkien on fairy-stories', a new expanded edition of Tolkien’s most famous, and most important essay 'On fairy-stories'. Accompanied by a critical study of the history and writing of the text.

J.R.R. tolkien's "On fairy-stories" is his most-studied and most-quoted essay, an exemplary personal statement of his views on the role of imagination in literature, and an intellectual tour de force vital for understanding tolkien's achievement in the writing of The Lord of the Rings. fairy-stories are not just for children, as anyone who has read Tolkien will know. In his essay On fairy-stories Tolkien discusses the nature of fairy-tales and fantasy and rescues the genre from those who would relegate it to juvenilia.

Next follows an interview with the authors of this soon to be released gem of Tolkien studies.

The Interview:

Q. What is the main difference between “On fairy-stories” by Tolkien and this book called Tolkien On fairy-stories?

To answer from the perspective of size, Tolkien’s essay “On fairy-stories” comprises about 18,000 words and takes up 57 pages of the 320 page book that is Tolkien On fairy-stories. The other 260-plus pages in the book include our introduction, our notes to the essay itself, a history of “On fairy-stories” from its beginning through its evolution in published texts, two newspaper accounts of the 1939 lecture, our transcriptions of two holograph manuscripts of the developing lecture/essay (plus commentary), two bibliographies (one our critical bibliography, the second a bibliography of works consulted or cited by Tolkien), and an index.

Q. How did Tolkien to write “On fairy-stories” in the first place?

In October 1938 he was asked to give the Andrew Lang Lecture at St. Andrews University for 1938-39. The topic was his own choice, and it wasn’t until February 1st 1939 that Tolkien set the date of the lecture and informed St. Andrews that his topic would be “fairy-stories”—the use of the preposition in the title “On fairy-stories” came some years later.

Q. Do the original drafts for the Andrew Lang Lecture at the University of St. Andrews, Scotland, in 1939, still exist?

To answer this, one needs to clarify terminology a bit. No version survives of the actual lecture, as delivered in 1939. However, the earliest draft of the lecture does survive. We call it Manuscript A, and a transcription appears in our book. The next stage we call Manuscript B. This is a much longer version of Tolkien’s thoughts, and the published essay is in one sense a condensation from the larger Manuscript B. Manuscript B shows evidence of parts having been written for oral delivery (i.e. a lecture) and parts in the transformation from lecture to essay— Tolkien seems to have worked and reworked this draft so that what was the lecture may survive as some kind of irrecoverable palimpsest underneath the layers of revision, most of which seems to have taken place in 1943. We include a transcription of Manuscript B as well as the large number of miscellaneous pages that are associated with that version. From there, Tolkien made a third manuscript, which we call C, from which the first typescript was made. Manuscript C and the typescript (made in August 1943 by Margaret Douglas, a friend of and typist for Charles Williams) are very close to the version of the essay as first published in Essays Presented to Charles Williams (1947), the memorial volume edited by C. S. Lewis. For reasons of space and repetition we did not include a transcription of Manuscript C or the typescript.

Q. Are there many new, unpublished, parts that will be published in this book?

Yes. Both Manuscript A (20 printed pages) and Manuscript B (around 45 pages), along its large number of miscellaneous pages (also about 45 pages), have never been published before. In many of these pages Tolkien discusses aspects of his topic that were not covered at all in the published essay as we know it.

Q. How does working on this lecture compare to working on The Annotated Hobbit and the extended edition of Smith of Wootton Major?

Because of its length and complexity Tolkien On fairy-stories was a great deal more difficult to work with than Smith of Wootton Major. In terms of size and endeavor it is somewhat comparable to The Annotated Hobbit, but the real difference lies in the fact that with Tolkien On fairy-stories we were working not only with a finished self-contained work, the essay “On fairy-stories”, but also with Tolkien’s research notes and early drafts of the developing lecture/essay. And because this is a work of non-fiction, rather than a creative work, there are concrete associations with the materials that Tolkien read up on and his reactions to these works as expressed in his drafts of the lecture/essay. For example, Tolkien’s earliest draft was written soon after Tolkien had encountered The Coloured Lands (1938), a posthumous volume of fairy-stories, satirical verse, pictures and commentary by G. K. Chesterton, and the influence of Chesterton is much more visible in the early draft than in the later published essay. But the real magnitude of difference between working on this book and either Smith of Wootton Major or The Annotated Hobbit was dealing with the process of transcribing Tolkien’s hastiest drafts. (With Smith of Wootton Major there were mostly typescripts.) That Tolkien wrote his initial (penciled) drafts very quickly and then would soon afterwards write over this in ink, also filling pages with cancels, corrections, inserts, and marginal notes, made for work of enormous complexity. When the reader encounters transcriptions on the printed page, everything seems measured and for the most part clear.

Q. What is the general purpose of creating this book?

To give readers, students and scholars of Tolkien the closest possible look into the development of this important essay, and a glimpse into tolkien's most considered thoughts on the subject.

Q. “On fairy-stories” might be the most-quoted essay from the hand of Tolkien, why do you believe this is so?

It is the most theoretical, and the most compatible with the overall body of his creative work. “On fairy-stories” is essential for understanding tolkien's own writings, and sets out many of his creative principles, among them sub-creation, the concept of Faërie, and the value of fantasy.

Q. Will “Leaf by Niggle” also be included in this book? Are there also different versions of this and will you also comment on it?

No, “Leaf by Niggle” was not part of this project. By the fact of that story having been published together with “On fairy-stories” in Tree and Leaf, it has acquired certain associations with the essay. But we think that Smith of Wootton Major provides a better encapsulation of Tolkien’s ideals as expressed in the essay. Of course, when Tree and Leaf was first put together in 1964, Tolkien had not yet written Smith. But Tolkien’s thought in reworking “On fairy-stories” for that volume clearly continued when he turned to the writing of Smith, and the result is fascinating.

Q. How was working on a project like this together? How did this cooperation work?

We’ve already worked together on five volumes of Tolkien Studies that we co-edit (along with Mike Drout), so in many ways this was an extension of a familiar process. Day to day things of working around each others schedules, emailing each other discoveries, swapping drafts and transcriptions, working through difficulties of readings and perspectives—it is all very engaging. We each brought different strengths to the project, and we think it’s fair to say that the end result is a better book than either one of us could have done on our own.

Q. In an interview with Alan Lee I talked about tolkien's vision on the use of “frames” (https://tolkienlibrary.com/press/823-interview-with-alan-lee.php), it seems these days this idea is being abandoned more or less. Is this just a question of taste or has the general view on “faerie” altered in modern society?

Tolkien felt that the conventional beginning and end of fairy-stories, “Once upon a time” and “They lived happily ever after” were artificial insofar as they took no account of the ongoing nature not just of story but of life. (See Sam and Frodo on the stairs of Cirith Ungol for more on this.) But he also recognized that any work of art must start somewhere and end somewhere, must have an edge or a line drawn round to define it. His own stories certainly have definite beginnings and endings, although they also hint at an ongoing story. We’re not convinced that this idea is being abandoned, nor that modern society has altered its view of faërie (if it ever had one).

Authors: Verlyn Flieger, Douglas A. Anderson

Type: hardcover

Estimate: 128 pages

Publisher: HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

Publication Date: 2 June 2008

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0007244665

ISBN-13: 978-0007244669

Spread the news about this J.R.R. Tolkien article: